“Of the beliefs and practices whether generally accepted or publicly enjoined which are preserved in the Church some we possess derived from written teaching; others we have received delivered to us ‘in mystery’ by the tradition of the Apostles; and both of these in relation to true religion have the same force. And these no one will contradict; – no one, at all events, who is even moderately versed in the institutions of the Church. For were we to attempt to reject such customs as have no written authority, on the ground that the importance they possess is small, we should unintentionally injure the Gospel in these matters…” ~Saint Basil

To Catholics, tradition matters. Rather, tradition should matter. What is tradition? There are many ways to define it that all stick to the same basic point. One could say that tradition is that which we receive from those who came before us. Of course, we must determine what is worth holding on to, i.e., the true and the good, and what isn’t. Honoring tradition is a sure sign of humility. We learn from those who came before us. You’ve no doubt heard the expression, “We stand on the shoulders of giants.” Well, that is a nod to tradition.

Within the Church, Tradition resides in the Magisterium, the official teaching of the Church on matters relating to faith and morals. The tenets of these core teachings must be adhered to in full by all Catholics. They cannot and will not change.

Faith: The Eucharist is the true Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ.

Morals: Abortion is always wrong.

No cherry picking allowed. Of course, many Catholics still pick and chose away.

Tradition can also be defined with a lower case “t”. These traditions, like sacred music, the rubrics of Mass, etc., don’t carry the same weight as the Tradition described above, but they are still very important, as they connect the living of today to a two-thousand year history. Those who honor tradition are often accused of being out of touch, antediluvian, stubborn, even irrelevant. But this attitude evinces something much worse than stubbornness; it betrays pride, implying that nothing helpful can be learned from the past except how not to be. “Boy, were they wrong or what!” This attitude presumes a secret knowledge, a gnosis, to the enlightened of today that was somehow blocked from all previous ages. The skepticism about tradition extends, perhaps most especially, to ancient liturgical practices.

There are some who argue that liturgy, specifically how it is celebrated, should be as malleable as a ball of hot wax. “The times change, so too should the liturgy.” Instead of being seen as a blessing and a gift, liturgical tradition (the use of Latin, Gregorian Chant, and even how liturgy was offered) was seen as a liability and an embarrassment. Democratizing liturgy, it was argued, was the best way to make ourselves relevant to the world today. Burn off the mossy accretions of two-thousand years, and we will fill the pews. It was bold, it was revolutionary, and it was a disaster.

For the past forty years or so, this bold tack was implemented across the board. Without Vatican approval, Latin was all but abandoned, liturgical music was made maddeningly banal, priests in their homilies abandoned substance and doctrine in favor of fluff and cringe-worthy jokes. Further, clerical roles were surrendered to the laity, and even church buildings themselves were radically reconfigured to emphasize the community instead of the Sacrament, and so on. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI described this phenomenon in the Church as a “hermeneutic of rupture” from the past. Rather than the implementation of modest, gradual reforms envisioned by the Second Vatican Council that would ensure a “hermeneutic of continuity” we witnessed bishops and priests in the United States presiding over a crazed period of liturgical upheaval and confusion. Chaos ensued.

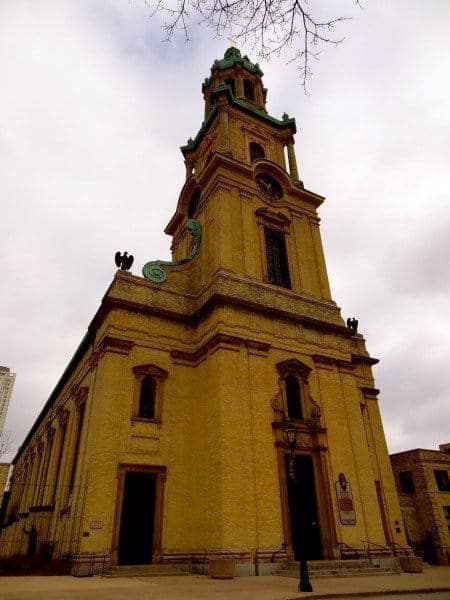

Milwaukee became one of the national epicenters of this radical experiment, as the machinations of the Weakland Regime savaged time-honored traditions, culminating in his jaw-dropping “renovation” of Saint John the Evangelist Cathedral. The architectural offenses to our archdiocesan mother church are a fitting, lasting and symbolic testament to Weakland’s disgraced legacy. His quiet, bookish persona masked a truly radical agenda that hindsight is only making more clear by the day. (While Weakland has long-since exited stage right, and good riddance, his loyal minions remain entrenched in countless bureaucratic and middle management positions. What’s been done to uproot them? Nothing really.)

For a while, this radical revolution seemed sustainable and unstoppable. But the coming of age of a generation of younger Catholics coincided with a German Cardinal’s ascension to the See of Saint Peter. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI knew that younger Catholics reared in the post-Vatican II chaos and uncertainty were desperately seeking a return to tradition and, by extension, a clear Catholic identity. Younger Catholics were well-aware of what contemporary culture was offering them, so they were immediately turned off to those in the Church who attempted to co-opt that culture by applying a light Catholic gloss to modern, passing fads and awkwardly grafting them on the liturgy. Then-Cardinal Ratzinger touched on this point years ago:

“It is also worth observing here that the ‘creativity’ involved in manufactured liturgies has a very restricted scope. It is poor indeed compared with the wealth of the received liturgy in its hundreds and thousands of years of history. Unfortunately, the originators of homemade liturgies are slower to become aware of this than the participants…” (Feast of Faith)

Younger Catholics pivoted away from priests offering patronizing pablum in their homilies instead of solid Church teaching and substance. Want proof? In Milwaukee, one of the parishes most marked by a growing number of young Catholics and young Catholic families is Saint Stanislaus, where the traditional Latin Mass is offered everyday.

Catholicism is not about reinventing the wheel. Legitimate changes in practice should be made with careful deliberation, and always in tandem with the college of bishops acting in union with the bishop of Rome. We are still waiting for the older generation of Catholics to catch up to what those of us a number of decades younger get instinctively. It’s the same lesson Saint Paul wrote down so many centuries ago: “Stand firm and hold fast to the teachings we passed on to you, whether by word of mouth or by the letter.” In short, tradition matters today.