I am haunted by Goldie. She lurks downtown in a school near the old Schlitz Brewery. She stands in the library on the Downer Avenue campus of the University of Wisconsin. She’s been with me on the cold streets of Kiev. She lies under cedars on a sunbaked hilltop in Jerusalem. Goldie from Milwaukee. Goldie, one of the most powerful women of the twentieth century, who lived her people’s dream. Goldie Mabovitch, North Side Jewish girl, brightest third-grader in the Fourth Street School. It’s called Golda Meir Elementary now.

Thanks to Goldie, people in Israel smile whenever I mention Milwaukee. But Milwaukeeans only stare when I mention Golda Meir. The woman in question was labor minister and foreign minister and, finally, prime minister of Israel. She guided her country through the Yom Kippur War. She responded to the terrorist massacre at the 1972 Olympics. Remember her?

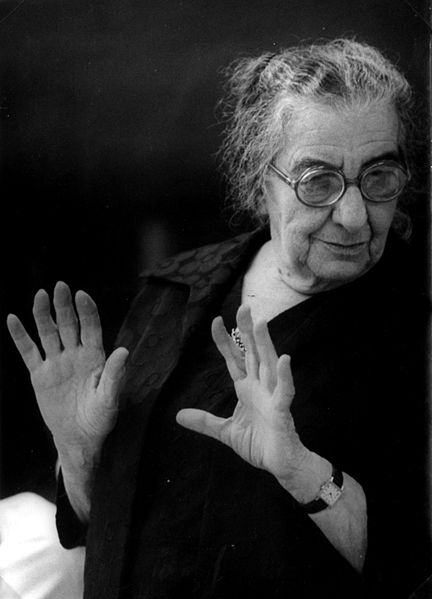

Steven Spielberg gave Golda an opening scene in Munich, where the great lady, wearing Lynn Cohen’s wrinkled skin, proves once again that the hand that governs armies can tip a teapot with finesse. Ingrid Bergman’s last film performance was in A Woman Called Golda. In the title sequence, the prime minister (Bergman in a wooly wig) clomps into a Milwaukee auditorium in her celebrated orthopedic shoes. The upright piano thrums as Black schoolchildren, pupils at Goldie’s brewery-side alma mater, sing the Israeli anthem in Hebrew. (This actually happened.) We owe Golda a second look.

This site has a Catholic point of view, and we dwell more on the Midwest than the Middle East, but we honor moral courage wherever it is found. Golda left Milwaukee and rose to global fame, driven all her life by tenacious values. She came to Milwaukee from Eastern Europe as a little girl. Her strongest Ukrainian memory, she wrote, was of her father boarding up their door to keep back rioters in a pogrom. Yet the violence and dislocation that marked her tender years would not control her: Golda had honor and she had guts. She says, in My Life, “To me, being Jewish means and has always meant being proud to be part of a people that has maintained its distinct identity for more than two thousand years, with all the pain and torment that has been inflicted upon it.” Today, the Ukrainians remember Golda politely: you can find a fine plaque near her birthplace in Kiev, next to a shoe store on Baseyna street. (If you go in January, as I did, take a hat.)

Although Golda and her family, like so many Jews of that generation, were not particularly religious, the teenage Goldie Mabovitch had a near-religious commitment to Zionism, the political movement to create a Jewish homeland. The initial connection was made in Milwaukee on Tenth Street and Center, where the future stateswoman joined the Labor Zionist Youth Movement at North Division High School. After graduating from the Milwaukee State Normal School (now UWM), Golda became a teacher. She met Morris Meyerson, a Jew and a socialist. They married in 1917 and emigrated to Palestine. Golda made Morris promise to move before saying “I do.”

Golda’s love of her people, her passion and zeal, carried her straight into the infernally hot chicken coops of a Galilee kibbutz. There must have been mornings when she wondered why she’d come. But, within a few years, her fellow farmers nominated her as their representative to the Histadrut, a powerful labor union that acted as a surrogate government. By 1948, when statehood for the Jews was imminent, Golda was a fixture of the establishment. She was one of two women signers of Declaration of Independence. She wrote: “After I signed, I cried. When I studied American history as a schoolgirl and read about those who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, I couldn’t imagine these were real people doing something real. And there I was sitting down and signing the declaration.” Golda was a long way from Milwaukee. Her convictions had carried her there.

If you visit Jerusalem today, get on the fancy trolley installed by Mayor Barkat. Glide by the ancient city in the air-conditioned tube and get off at the end of the line: Mount Herzl. Head through the gates of the national cemetery on the crest of the hill. At the highest spot among the graves, on a huge square of white pavement, there is a black granite polygon marked with four Hebrew letters: hay, resh, tzadi, lamed: Herzl, the father of modern Israel. Move on.

Down a winding path, you will see a low stone marker. It’s not grand. It’s Goldie. Think of how this Milwaukee girl got to this place overlooking the pines of the Jerusalem Forest. Put a small stone on her tomb, following Jewish custom, and tell her you remember her. Pray for peace. Pray for courage, too, as you remember Golda’s words: “We will build Israel with decency and dignity, and one day our present detractors will come knocking at our door.” Milwaukee could use more like Goldie Mabovitch.