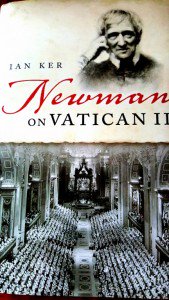

Noted theologian and Newman scholar Ian Ker recently wrote an excellent book, Newman on Vatican II. Cardinal Newman, who died in 1890, was of course not around for the Second Vatican Council, but many have correctly proposed that he was prescient by broaching subjects that the Council was to take up over half a century after his death. The most fascinating chapter in Ker’s book is entitled “Secularization and the New Evangelization”. Based on Newman’s writings, Ker speculates how he would have approached evangelization today, in our post-Christian, thoroughly secularized culture.

Noted theologian and Newman scholar Ian Ker recently wrote an excellent book, Newman on Vatican II. Cardinal Newman, who died in 1890, was of course not around for the Second Vatican Council, but many have correctly proposed that he was prescient by broaching subjects that the Council was to take up over half a century after his death. The most fascinating chapter in Ker’s book is entitled “Secularization and the New Evangelization”. Based on Newman’s writings, Ker speculates how he would have approached evangelization today, in our post-Christian, thoroughly secularized culture.

Newman was a realist. Even in his own day, he saw the exploding secularization of culture and quickly identified the conditions as unique in history.

The trials which lie before us are such as would appall and make dizzy even such courageous hearts as St. Athanasius, St. Gregory, or St. Gregory VII. And they would confess that, dark as the prospect of their own day was to them severally, ours has a darkness different in kind from any that has been before it. [Christianity had] never yet had experience of a world simply irreligious…

“A world simply irreligious.” Newman wrote this in the 19th century and, since then, we’ve gone into overdrive on the “simply irreligious” or “I’m spiritual but not religious” theme. It’s not hard to imagine what Newman would say about the present state of “gender fluid”/ trans-whatever, in which the most basic questions of morality (and reality) are thrown into question.

In a world as confused and off-track as our own, what would Newman propose in terms of evangelization? What solution would he offer? What plan of action? What is needed, according to Ker, is “a response to secular man’s sense of unfulfillment and desire for happiness.” In this we hear an echo of Saint Augustine who, centuries earlier, wrote the immortal lines, “Our hearts were made for Thee, Lord, and they are restless until they rest in Thee.” This tracks closely to Newman, who wrote, “The affections require a something more vast and more enduring than anything created.” And, “Our hearts require something more permanent and uniform than man can be . . . Do not all men die?” Ker writes, “It is when we understand the true nature and needs of the human person that we understand that there must be a personal God.” (Emphasis added.) You don’t need to have an advanced degree in theology to arrive at the answer to Who this personal God is: Christ himself, true God and true man. Christ is the only answer to our deepest longing.

Citing Newman, Ker observes that “Christianity of all the religions in the world alone ‘tends to fulfill’ human ‘aspirations, needs,’ for it is Jesus Christ who ‘fulfills the one great need of human nature, the Healer of its wounds, the Physician of the soul’.” Why have so many Catholics left the faith? The answer is not too difficult. Ker explains,

The reason, Newman thought . . . why so many Catholics abandon their religion is because “They have not impressed upon their hearts the life of our Lord and Savior as given us in the Evangelists”, they do not believe “with the heart”, and lack “a faith founded in a personal love for the Object of Faith”.

We take our eyes off Christ, found in-the-flesh in the pages of Scripture. The Gospels, especially in their account of Christ’s passion and death, remind us how real Christ’s humanity is. “It was because God had become man in the form of a particular Jew living in a particular place at a particular time that it was possible for a man to actually strike his creator.” (Emphasis added.) It’s a powerful statement. To underscore the bond between humanity and Christ, Newman brings the reader into the depths of Christ’s passion. He shows us how Christ’s perfect human nature made the torments of His passion even more intense, physically and especially mentally.

Our Lord felt pain of the body, with an advertence and a consciousness, and therefore with a keenness and intensity, . . . because His soul was so absolutely in His power, so simply free from the influence of distractions, so fully directed upon the pain, so utterly surrendered, so simply subjected to the suffering. And thus He may truly be said to have suffered the whole of His passion in every moment of it.

So before all else, a rediscovery of Christ, true God and true man, in Scripture and Sacrament, is essential to any effort of evangelization. Ker warns against a very popular trend today, as in Newman’s day, which is the tendency to relativize Christ and His teachings based on one’s “personal relationship” with Him. Newman’s emphasis on discovering Christ at the personal level in Scripture should not be confused with a Protestant, anti-hierarchical faith. Ker writes, “Newman thought that, if there was a ‘leading idea’ . . . of Christianity, then the Incarnation was ‘the central aspect of Christianity, out of which the three main aspects of its teaching take their rise, the sacramental, the hierarchical, and the ascetic‘.” Christ cannot be cleaved from the sacramental and hierarchical aspects for the sake of one’s personal preference. Pope Francis, echoing Pope Paul VI, said the same thing. “This is why the great Paul VI said that it is an absurd dichotomy to love Christ without the Church, to listen to Christ but not the Church, to be with Christ at the margins of the Church. It’s not possible. It is an absurd dichotomy.”

How often today do we hear Christianity’s demand for love of neighbor used as an excuse to approve acts which are contrary to traditional Christian teaching? President Obama claimed that it was the Golden Rule and Christ’s call to love, that was the main reason prompting him to change his view on same-sex “marriage”. Ker addresses this relativistic take on Christianity head-on.

It was not just that Newman wanted to make the person of Christ real to his hearers; he was also well aware of the perennial tendency of every age and society to look at Jesus from the perspective of their own concerns and preoccupations: “The world . . . in every age . . . chooses some one or other peculiarity of the Gospel as the badge of its particular fashion for the time being. . . .” In a modern civilized society which prides itself on its compassion and concern for human rights, there was the danger of a soft kind of Christianity, lacking in “firmness, manliness, godly severity”. Newman thought that this deficiency led to a distortion of the virtue of charity, in so far as an ‘element of zeal and holy sternness’ was needed ‘to temper and give character to the languid, unmeaning benevolence which we misname Christian love’.

So the turning of one’s personal relationship with Christ into a personal stamp of approval of one’s moral choices in the name of Christ is definitely not in the cards for Newman’s proposal. When you hear people talk about making Christianity “relevant” for our times, what is usually meant is the accommodation of the traditional faith to our own personal feelings and impulses. Our relationship with Christ should actually enhance the awareness of our sins, not cover it up. According to Newman, “Your knowledge of your sins increases with your view of God’s mercy in Christ.” The popular tendency to talk about Jesus, and never about sin is extremely dangerous. Ker cites one of Newman’s most sobering warnings about the danger of ignoring sin’s lethality. “And this is what sin does for immortal souls; that they should be like the cattle which are slaughtered at the shambles, yet touch and smell the very weapons which are to destroy them.”

A return to the contemplation of Christ is essential to evangelization. Cardinal Robert Sarah is a modern-day Cardinal Newman, who places great emphasis on our bond to the Word as a result of the Incarnation. Throughout much of his outstanding book, God or Nothing: A Conversation on Faith with Nicolas Diat, Sarah continually returns to the theme of Christ’s humanity and our need to encounter Him in our post-Christian era. In one passage of his book, the parallel to Newman is striking.

Indeed, when we observe today the many deficiencies of faith, the eclipse of the sense of God and of man, the lack of real familiarity with the teachings of Jesus Christ, the detachment of some countries from their Christian roots, and what John Paul II called a “silent apostasy”, it is urgent to think about a new evangelization. This movement presupposes that we go beyond mere theoretical knowledge of the Word of God; we must rediscover personal contact with Jesus Christ. It is important to give individuals the opportunity for the experience of close encounters with Christ.