Pope Pius XII called Dietrich von Hildebrand “the twentieth-century Doctor of the Church”. Pope Benedict XVI is also a great admirer. Dietrich von Hildebrand (1889-1977) was a prolific writer and professor who lived through much of the last century’s most historic events. Over the course of his long life, through thirty books and countless articles and lectures, he accurately warned the world about the dangers of Communism and secularism. He was also a strong voice of clarity in the Church during the tumultuous years of the ’60s and ’70s. Alice von Hildebrand carries on his legacy in many ways to this day.

I’m reading von Hildebrand’s Trojan Horse in the House of God. (For just one buck, it was a used bookstore bargain.) The book is a collection of essays on the errors of progressivism; errors that were widespread in his day and remain so in our own time. In the introduction, von Hildebrand gives the reader a preview of the pages that follow.

This book is addressed to all those who are still aware of the metaphysical situation of man, to those who have resisted brainwashing by secular slogans, who still possess the longing for God and are still conscious of a need for redemption.

In the chapter entitled “Fear of the Sacred” von Hildebrand harshly criticizes the whitewashing of external reminders of the sacred from liturgy. This was supposedly undertaken to make the liturgy more familiar and palatable to the average modern Catholic. We can better connect with Joe Catholic, so the argument goes, if he sees us just as he sees things in his everyday life. The interiors of church buildings and liturgy itself began to showcase this re-orientation of focus. The “in-the-round” design became popular, breaking away from the traditional linear/cruciform layout of Catholic churches. Communion rails were ripped out because they were seen as obtrusive impediments for the laity to access the sanctuary. Sanctuaries began to resemble stages from a talk-show. The priest pivoted to the people instead of the ancient practice of facing east (always symbolic of Christ). Latin, the official language of the Church, was abandoned. Beautiful vestments and sacred art were removed and/or destroyed. Chant was swapped for schmaltzy hymns, guitars and pianos. Holy Communion was distributed in the hand, and by many lay “ministers” instead of on the tongue while kneeling and exclusively by the priest. Many priests took on an overtly informal air, sometimes working the parishioners like a politician or talk-show host works an audience. Homilies based on doctrine and catechesis were replaced with dumbed down, folksy and irrelevant anecdotes about the day in the life of the priest. (Not surprisingly, clerical narcissism rose during this time.) All this, and more, was done because it was thought that people would better relate to a church that mirrors the conventions and expectations of the modern world. Von Hildebrand disagrees.

Many priests believe that replacing the sacred atmosphere that reigns, for example, in the marvelous churches of the Middle Ages or the baroque epoch, and in which the Latin Mass was celebrated, with a profane, functionalist, neutral, humdrum atmosphere will enable the Church to encounter the simple man in charity. But this is a fundamental error. It will not fulfill his deepest longing; it will merely offer him stones for bread.

Von Hildebrand contests that deep in man’s heart is a profound longing for transcendence, beauty, and also for visible reminders of the difference between the day-to-day and the exceptional. In liturgy, these mysteries are best expressed through the prayers, symbols and rubrics that have organically developed over the two-thousand year history of the Church. To deny man this encounter through a process of rupture, de-mystification and iconoclasm would be a profound disservice to that inner search.

Their [progressives’] “democratic” approach makes them overlook the fact that in all men who have a longing for God there is also a longing for the sacred and a sense of the difference between the sacred and the profane. . . . If he is a Catholic, he will desire to find a sacred atmosphere in the Church.

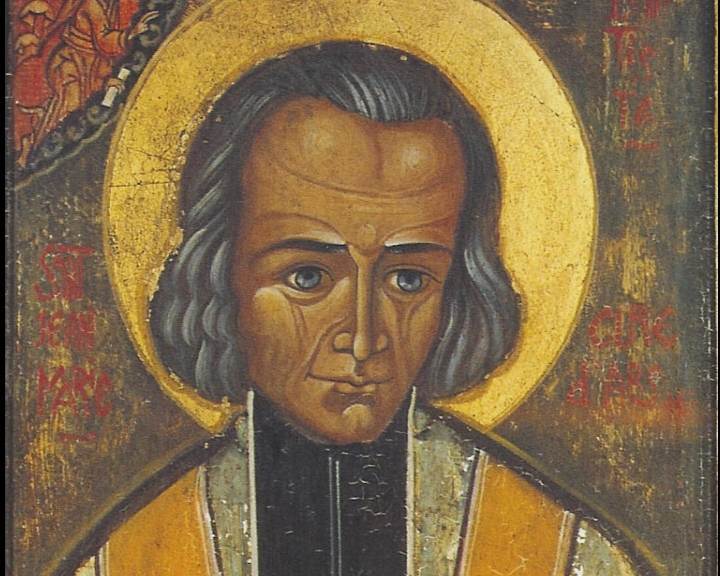

As for the priests, von Hildebrand writes, they should “emanate an atmosphere other than that of the average layman.” They should manifest “the spirit of reverence, the fusion of humility with a demeanor appropriate to the sacred office.” The best example for priests, he argues, is to look to the timeless Saints of the Church, not the base standards of today.

(Featured photo by Ernst Haas/Getty.)