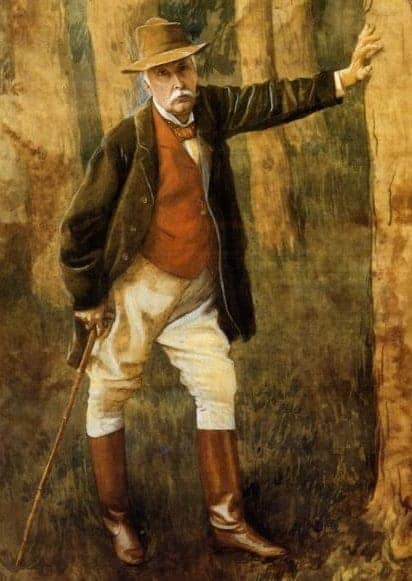

He was born in 1836 in Nantes, one of the four pillar-cities of the ancient Duchy of Brittany, to a rich cloth merchant and his wife. Brittany is, to this day, one of the most Catholic regions in France. Jacques Joseph Tissot had good Catholic parents and was a good Catholic boy. He became a good painter and not such a good Catholic.

But, though he took his time, he eventually handed over his brushes to God. And in the latter years of his life, Tissot showed the Lord in a way no one had before — and no one has duplicated since.

For some reason, Jacques loved all things English. By the time he was 20, most people knew him as “James.” One imagines he was a little pretentious. He went to Paris to study art.

This was not yet the time of the Impressionists, much less the Moderns — James was educated by copying paintings in the Louvre, just like everyone else. At 23, he painted four scenes from the Middle Ages — some based on Faust — which he exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1859. It was all very conventional.

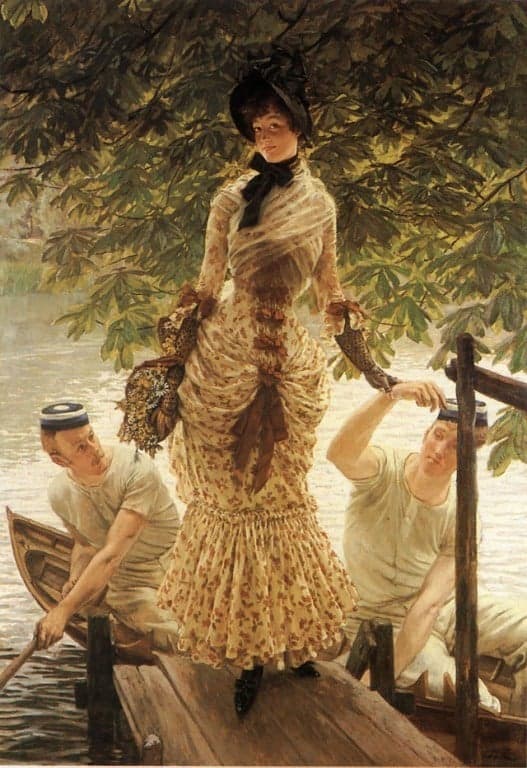

The young Tissot wanted to live by his art, and all the real money was in vanity. There was no Paris Hilton in 1860s Paris, but there were plenty of gold-flake beauties and spoiled, swanning dolls. Tissot wasn’t the only one to make a career out of these boobies. He was an oil-paint iPhone for the selfie-snappers of his day. Some have suggested that his childhood around dad’s cloth business helped him here: James painted with relish every fold in the wasp-waisted gowns of this sitters. The women loved it.

Then came a disastrous war, and the Paris Commune. Tissot fought against the Prussians in 1870 (France lost) and joined the Commune (some suggest, for economic reasons). As everyone knows, the Commune became associated with unsavory political and moral notions and ended in flames. James Tissot, anglophile, decided it was time to travel to the home of his tweed jacket. He landed in London in 1871.

In London, more calico and watered silk and pink chiffon and leapt off Tissot’s brush. The toffs adored him, and soon he was moving into a house in Saint John’s Wood.

To look at the pictures of this time, you would never guess the man had known suffering. All the world’s a salon — or a ballroom. Unless you’re on the riverbank with your suitors…

…or leaning on the rail of a ship in perfect whites.

It paid the bills. Edmond de Goncourt, the critic for whom the literary prize is named, visited London and observed tartly that there was always a big bottle of champagne on ice for the ladies in Tissot’s waiting room. (Sneer he might; it beats a Snickers from the vending machine.)

But champagne goes flat. In 1882, the divorcée with whom he has been living — and with whom he had conceived a son — died of consumption. He moved back to France, convinced that happy days were behind him.

Then, in 1885, when he was nearly 50, James Tissot had a Saint Paul moment. He experienced a reconversion. We don’t know why or how, but he came back to the Faith. Deo gratias.

It was a good time to be Catholic. In reaction to the Masonic madness of the Third Republic, a Catholic revival was sweeping France. Huysmans would soon convert. Thérèse Martin would soon climb Mount Carmel. Lagrange was active in biblical sciences. Everyone was reading the Vicomte de Chateaubriand’s work from two generations before, The Genius of Christianity.

That genius touched James Tissot. You can see the record in paint: the Spirit moved on Tissot’s canvasses and chiffon moved out.

But first the artist went on pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

In 1886, 1889, and 1896, James Tissot steamed across the Mediterranean to what was then Ottoman Palestine, to study the landscape and the architecture and the people. Like the natural scientists of his day — like an ornithologist in the Amazon or an anthropologist among the Xhosa — he produced hundreds of careful sketches of lined faces and cracked facades and sun-baked landscapes. He recorded reality. And as he frowned over details, he let the whole expanse of the Land of Israel into his bones and his bloodstream.

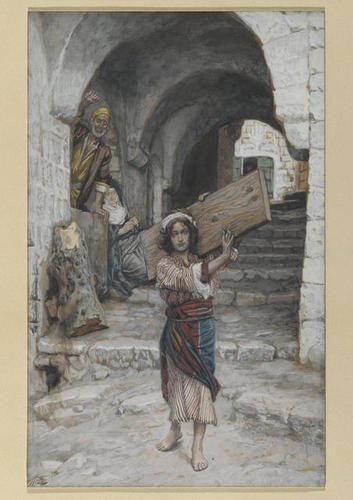

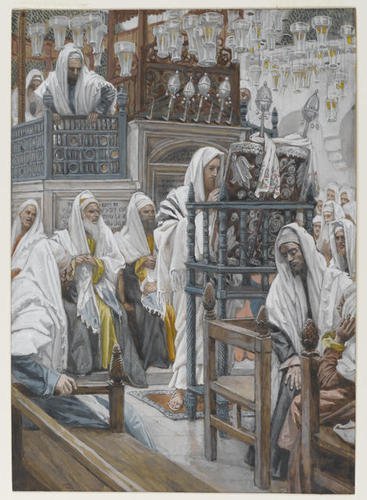

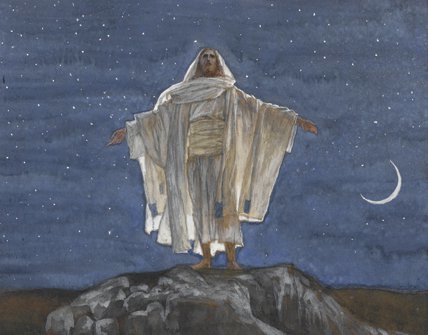

The result was over 300 finished works in gouache, which he showed in Paris in 1894-95. They then moved to London. They ended up in the Brooklyn Museum. The paintings caused uproar everywhere. It’s easy to see why.

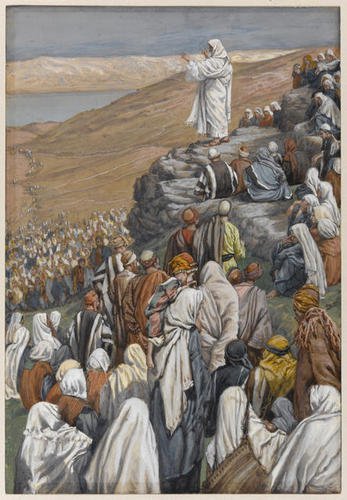

Jerusalem, here is your God:

These are from a series he called “The Life of Christ.” There’s no idealized, abstracted superhero Jesus here. No Nordic Christ. These are Semitic paintings.

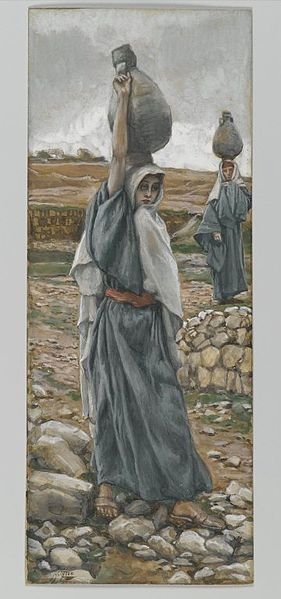

Tissot also knew Mary. Here is the Virgin as a young girl:

And here she is at the Annunciation — unlike any you’ve ever seen:

These paintings are realistic. They’re psychologically realistic, first of all. Just look at the Annunciation: Mary is slumped against a wall as she receives Gabriel’s news, the way people at adoration slump against a pew. Awe does that to a person. God exhausts you. You have to pray to know that.

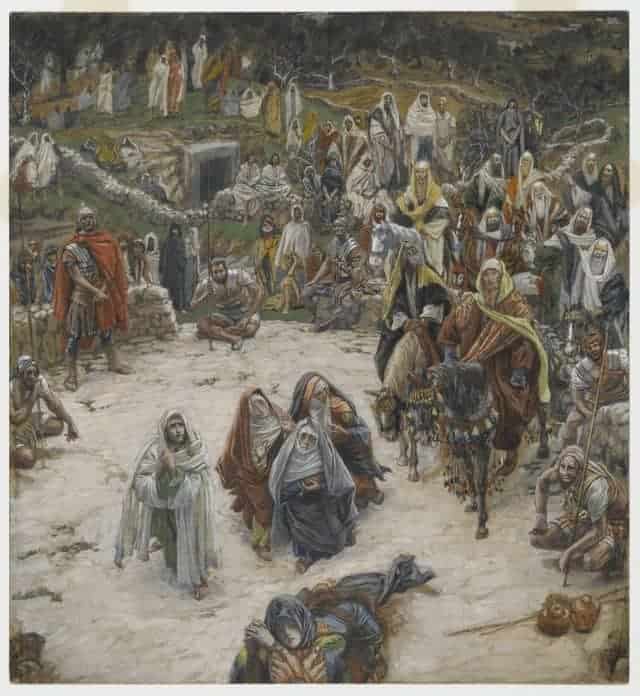

The scenes are also geographically realistic. You might think the natural splendor in these paintings, like the backgrounds in Renaissance portraits, springs from the artist’s imagination. It is beyond beautiful, but this is exactly what the Holy Land looks like. Ask anyone who’s been there to take a look. They will recognize landmarks natural and manmade — the Dead Sea and the Judean hills, the Lions’ Gate and the Citadel of David. It’s all so real.

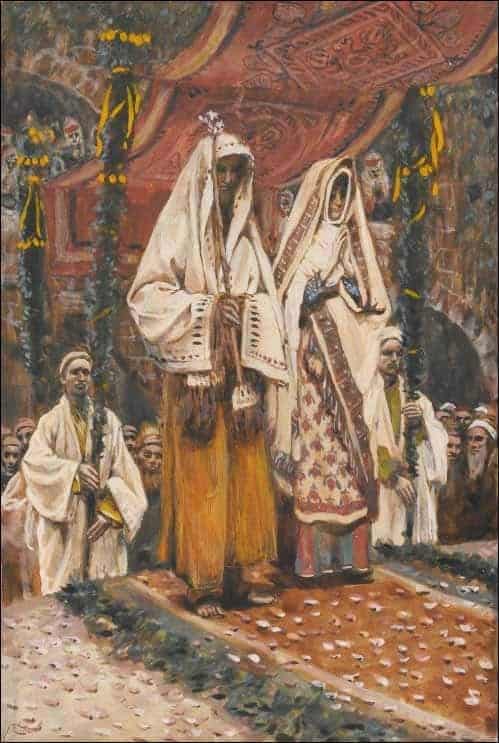

And the people in these images are authentic. They’re anthropologically correct. Look at Mary’s betrothal to Joseph. An Israeli of our century might think this was a Yemenite Jewish wedding:

Tissot gives us a Hebrew Mary and Joseph and a very Jewish Jesus. Better to say: he restores Jesus’s Jewishness to Our Lord. Because that’s how it was, for real. And it’s beautiful.

It’s beautiful because it is of God. God joined himself to Israel. Jesus was born on the fringes of the Roman Empire to a poor couple with an unfashionable monotheistic religion. God came to us in a particular time in a narrow little place on the ledge of the Levant. This is our Jesus.

Tissot spent the last years of his life working on subjects from the Hebrew Scriptures. (These can be seen today in the Jewish Museum in New York.) He exhibited 80 paintings in Paris in 1901. He never finished the series. The artist died suddenly in the summer of 1902, in the Château de Buillon in Doubs, a former abbey he had inherited from his father. His grave is in a chapel on the grounds.

James Tissot met the Lord in Paris, then followed Him to Palestine. I first discovered his works on colored plates protected by tissue paper in a huge volume from 1898 — the illustrated Bible that made Tissot’s reputation. The tome was on a high shelf in the limestone-walled library in the cellar of the Ecole Biblique, a renowned center of scholarship built in Jerusalem by French Dominicans between 1880 and 1900 — while Tissot was in town. I was a lowly volunteer shelver in this papery-smelling sanctuary. I stopped my work to gawk at this book.

I can’t help but ask: why did I have to wait to get into that library to discover Tissot? Why are his gouaches stocked away in Brooklyn, not hanging over the altars in churches where the parishioners have a little taste? Maybe it’s because, more than a century after his death, we’re not ready for Tissot. Tissot knew God Incarnate, and the reality of the Lord’s coming has always frightened us. We didn’t want to see it at the time — which is why we crucified Him — and we don’t wish to contemplate it now.

But we can fix that. We can let the Lord into our hearts. All we have to do is look.