I recently read an article in the Guardian about a new fad: curating one’s death. Two concrete practices of the fad illustrate what I mean by ‘curating one’s death’.

The first is the Swedish practice of döstädning, which is ‘death-cleaning’. The aim of the practice is, first, to keep our secrets secret by getting rid of whatever skeletons we’ve been keeping in the closet (literal or figurative)—maybe by burning our diaries or shredding photos of secret lovers. A second aim of the practice is to minimize the stuff we have so that our beneficiaries won’t fight over it. In other words, we can divvy up or toss the heirloom china and the diamond earrings before we die so that adult children won’t become estranged over who gets what.

A second trendy death practice is opting for the Infinity Burial, rather than a traditional casket or cremation. The Infinity Burial works like this: When a person dies, she is buried in the Infinity Burial Suit. The suit is a biodegradable garment woven with mushrooms and other microorganisms that feed on dead human tissue, turning the human cadaver into plant food. The fungi neutralize toxins found in the human body, like mercury, that would have been released into the environment in case of an ordinary burial or cremation. Users of the suit, thereby, reduce the environmental impact of their death. The developers of the Infinity Burial Suit also began the Decompiculture Society, which “promotes intimacy with and acceptance of the physical realities of decomposition as vehicles toward death acceptance.” They acknowledge that we’re all going to die and think that we should come to accept this and take responsibility for our personal impact on the planet.

Now, there’s something distressing about this faddish obsession with death and also something deeply right-ordered. It’s distressing that preparing for death is a trend, as trends come and go (and death isn’t a come-and-go sort of thing; it’s inevitable). It’s also distressing that some people are treating death as something to be controlled and curated, from hiring ‘death doulas’ to selecting the music and menu at the funeral reception. What’s right-ordered is the notion that death is something for which we should prepare.

Both philosophy, at least as it once was practiced, and our Catholic faith share the notion that death is something for which we’re to prepare. Let’s consider just two exemplars, one from philosophy and one from the Catholic tradition.

First, there’s Socrates. As Plato recounts in the Apology, Socrates is charged with impiety and corrupting the youth. He’s found guilty and sentenced to die. Plato writes about Socrates’s final days in his dialogue the Crito. In this dialogue, Socrates’s friends tell him that they can help him escape execution. It would mean exile for Socrates—a life on the run and a life of undermining all he stood for, e.g., personal integrity and pointing out untruths, inconsistencies, and vices in Athens. Socrates opts to take the poisonous hemlock and die. He dies standing for what he believes in; he dies virtuously and in a way that was consistent with how he lived.

What Socrates shows us in his final days is his philosophy of life: “The most important thing in life is not life, but the good life” (Crito 48b). And, in practice, he shows us that this good life includes a good death.

A difference between Socrates’s notion of a good death and today’s faddish death is this: For Socrates, we ought to prepare for a good death by living life virtuously. Virtue is what counts. For those swept up in today’s death obsession, what counts is not being a burden on our families or the environment after we die. While purging our homes of unnecessary things and concern for the environmental impact of our death are probably good in themselves, they’re inadequate preparation for death. What Socrates shows us is that we die well by living well—by living virtuously. So, one thing that’s missing in the current fad is adequate attention to the state of one’s soul, even at a natural level. Preparation for death involves a whole lot of thinking about what sort of person I am, what sort of person I want to be, and what sort of person I want to be remembered as.

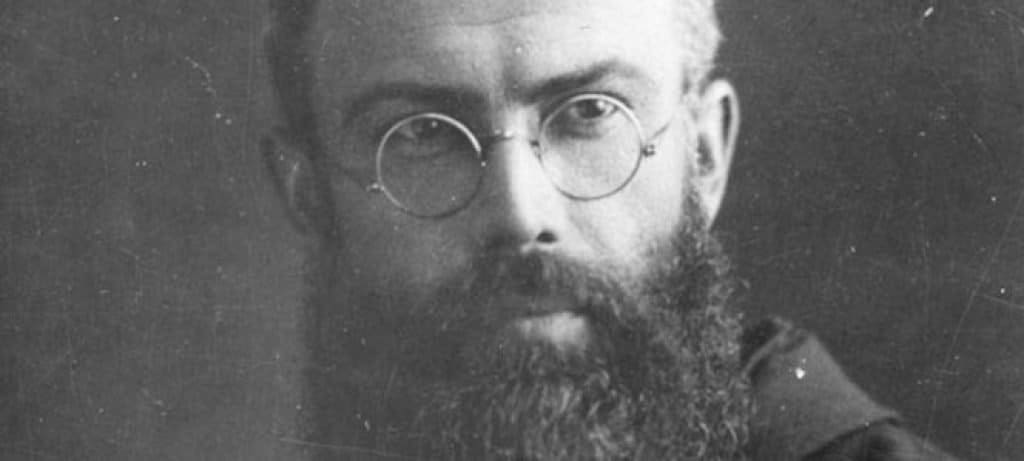

From within our Catholic tradition, we have countless examples of those who prepared well for death. Among them are all the martyrs. Take St. Maximilian Kolbe as a modern-day example. Maximilian Kolbe was a Polish Franciscan priest interred at Auschwitz. When a prisoner escaped from the camp one day, the Nazis selected ten prisoners to be starved to death as a way to reassert their authority. Maximilian Kolbe volunteered to take the place of one of the ten men chosen to be killed, and he died at Auschwitz in 1941.

For St. Maximilian Kolbe, preparing for death was a lifelong enterprise. Death was but a step on the way either to eternal union with God or eternal separation from Him. St. Maximilian Kolbe prepared for death throughout his life by continually committing himself to God, receiving grace, and living virtuously.

The current obsession with death is a positive step away from the death-defying culture that seeks to preserve one’s body and one’s consciousness indefinitely. It reminds us that we, too, will die and ought to prepare for this death. Where the movement falls short is in its understanding of who we are, as human beings, and what sorts of things we need to do to prepare for death. Both Socrates and great saints like Maximilian Kolbe agree that human beings are immortal in a very literal, individual way. This is not merely a pseudo-immortality gained through making sure our progeny think well of us and through minimizing our toxic footprint. For them, the best way to begin preparing for death is to examine how we’re living now. And that’s really the question for us: Are we living a life that is responsive to grace, a life that reflects a total and unwavering commitment to love God above all else and to love our neighbor?