Does it make you squirm? Here is the Virgin Mary, the Madonna, Our Lady — in a state of undress. Motherhood is well and good, but do they actually have to show it?

These are images of the Madonna Lactans, the Nursing Madonna. She is known to Greeks as Γαλακτοτροφουσα (Galaktotrophousa) and to Russians as Млекопитательница (Mlekopitatelnitsa). This is one of the oldest and most durable depictions of Mary in the Church. It was described by Saint Gregory the Great. And the fact you didn’t grow up with it has more to do with Queen Victoria and her caricatured conventions than with the Queen of Saints.

We need to reclaim an image that captivated generations of Christians. There is no reason to be intimidated by someone else’s prudery. Let’s swallow hard and take a look.

“And it came to pass, as he spoke these things, a certain woman from the crowd, lifting up her voice, said to him: Blessed is the womb that bore thee, and the paps that gave thee suck.” (Gospel of Luke, 11:27)

Mary really was the mother of Jesus. Jesus, the Christ, really was Mary’s baby boy. The unnamed woman in the crowd in Luke’s Gospel understood that. So does the Church. When we affirm the reality of this bond — between Mother and Son, between God and humanity — we avoid all kinds of ancient heresies and modern ideologies that can poison our Faith.

Some folks have a hard time with Christ’s humanity. Take the Docetist heretics of the first Christian centuries. According to them, Jesus only appeared to be a man of flesh and blood. His body was a phantasm. Perhaps He was something like a Hindu avatar, or Zeus appearing as a bull. After all, could God lower Himself to take a human body, for real? Surely not. God never was human and never actually died. The very idea seemed gauche.

Of course, the Fathers of the Church thought differently and Docetism was vehemently rejected at the Council of Nicaea in 325. Centuries earlier, Ignatius of Antioch attacked the Docetists in his letter to the Smyrnaeans:

“They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ…. They who deny the gift of God are perishing in their disputes.” (Letter to the Smyrnaeans 7:1, circa 110 AD)

“They who deny the gift of God.” That is what we do when we look away from Jesus’s humanity. When we close our eyes to the helpless baby reaching for his mother’s breast. We don’t want to allow God to be quite so generous.

Docetism is not dead. In our own century, we have inherited the prejudices of the 18th century, with its worship of Reason, and the pretensions of the 19th century, when Science was god. We drink in Kant and Hegel with our mothers’ milk. How can we swallow Mary and Jesus?

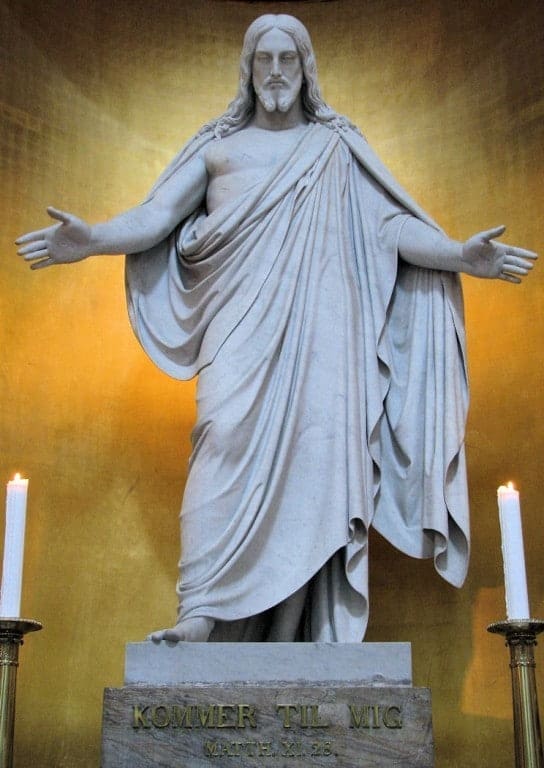

The modern Docetists have the fix. Can’t believe in Jesus the Nazarene as true God and true Man? How about imagining him as a sort of ideal human, a Superman or Übermensch? Seems less déclassé. Many liberal Protestants can’t stomach the Incarnation — not really — but they can dream of the Lord as a sort of radiant Ideal. This statue of Christ carved in Denmark in 1821 by Bertel Thorvaldsen has been cloned all over the Protestant world. The Mormons like it, too:

Jesus as He-Man. That’s an image we like.

We like it, but it’s a trap.

The little Lord Jesus, mewling and puking. Mary, His Mother, giving Him lunch and changing His wet drawers. This is the way God chose to come to us. No glowing white bodybuilders from Krypton are mentioned in Scripture.

The Madonna Lactans saves our faith in Christ’s humanity; in his Incarnation. And that matters. Because in assuming our humanity in all its fragrant fleshiness, Jesus made us fit for Heaven.

Saint Thomas says: “The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods.” (Thomas Aquinas, Opusc. 57, 1-4. Compare Saint Athanasius, De inc. 54, 3: PG 25, 192B. See Catechism of the Catholic Church number 460.)

Adam said of Eve: “This now is bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh.” (Genesis 2:23). Mary and Jesus had the same relationship. Jesus has this relationship with every human one of us.

Now, there’s another problem here, and it would be wimpish to end our art-historical spelunking without facing it:

Why are we afraid of Mary’s breasts, really? Because we, like Adam and Eve, have sinned. And now we’re hiding in the bushes trying to sew some leaves together to hide our nakedness.

Yes, this is indeed the 21st century. We no longer worship Reason or Science, we’re really keen on Sex.

Perhaps those bare breasts remind us of oily magazines and slippery billboards. They bring up clammy ghosts from the sidewalks and poolsides and monochrome malls of our immodest cities, where body parts are dumbly displayed. For us, breasts mean pornography and pop-stars and plastic surgery.

But that’s only because we’re sick.

These are not those breasts. Look again at these images, taken from disparate centuries and cultures that are worlds apart. The Christian people is crying for its Mother. Mary needs to feed her baby, and she does so — very naturally. We can learn from that.

Bernard of Clairvaux, the Medieval revolutionary, was tired. He was sick and partly blind. In a cold stone chapel somewhere in France, he flopped down on his knees before a statue of the Madonna. He tried to pray and ended up singing, but even his voice was weak. As he croaked a line in the famous Gregorian hymn, “Monstra te esse Matrem” (“Show yourself a Mother”), Mary moved. The transfigured statue pressed her breast and sent a spout of milk down on the hairy old monk. His lips were wetted and he sang with vigor. The milk soaked his eye, and it opened for the first time in months. He was healed.

These breasts can nourish us. Our Mother can heal us. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.