More than books — more even than the Bible — buildings bring a message into the public space. The best buildings bear a message about man and a message about God. Just look at the ancient Temple of Jerusalem.

When I first devised the article below back in 2013, I just thought myself clever. I had discovered that so many buildings in our city whisper (or shout!) of the culture and the values of Christendom.

The assumption of the 80s, when I was a child, and the 90s, when I was a student, was that these buildings had stood and would ever stand. Our only burden was to be bored of them.

How the world has changed.

Over the past five weeks, beautiful buildings were torched. Copper lampposts and iron grilles bit the dust. Statues that stood for a century have been yanked down with lassoes while the state stood by.

They’re attacking architecture and art. Why? Because they share our intuition about its meaning.

And what do we do? One thing we have been taught is to be silent. We’re supposed to feel ashamed: that will keep us docile and ready for the yoke. Buildings like those in this article are supposed to be a source of our shame. Maybe it’s easier to bulldoze them?

It won’t end with a building. First they dumped the statue in the harbor, next they’ll dump you. And anyone who is spiritually connected to our past — anyone who even looks like he could be descended from someone connected to Western, and therefore Christian, civilization — is marked for destruction. So it was with the aristos in old Paris and the kulaks in the wheatfields of Ukraine.

Will we go as they went, stunned and silent? God forbid! We may be brought low; we don’t need to cooperate in our own abasement.

Perhaps we won’t go without a fight. Perhaps we will defend what is good. We can start by defending our buildings — culture in physical form.

Because culture is where God is.

As the son of God took flesh and became a little child, so, by analogy, a column or a cupola can cradle a speck of the divine.

We embrace the truth. We will announce the truth. Plenty of Milwaukee buildings have given good example.

*********

Milwaukee is — or was — a city of children, churches, and cheese. At its best, it is plainspoken and decent and solid: people here still think of themselves like that, and they’re not half wrong.

But those who know this city know, too, that it can be a place of secret codes, of ineffable longing for the far-away and subtle signals that only the keen eye sees.

A lot of these signals emanate from Milwaukee’s buildings. We call them Milwaukee Wormholes. These are magic portals that can zip you to another place and time, if only you know how to enter.

When you grow up here, of course, you take it all for granted: City Hall is just a filing cabinet; the Central Library a bin for books.

But when you begin to travel you find that the buildings of Milwaukee have prepared you for the trip. Is this Leipzig or Wisconsin Avenue? Dresden or Cathedral Square? Rome or Lincoln Avenue across from the Serbian restaurant?

Though it’s not in our nature to tout it, Milwaukee’s got architectural chops, and most of the best buildings went up just a few decades after the wigwams were rolled away. They were built by displaced Europeans. The longing of exile limns the lintels like scrollwork. It frosts the acanthus leaves on every Corinthian shaft. The anxiety of civilized men huddled on the fringes of their world added spiritual urgency to the work of the plumbline and the square.

Now embarrassed with a richness of grand buildings, our city teaches gently — almost undetectably — just like the best teachers do. It says: there is more. The world is wider than Water Street. Forget not my cousins, far from here.

Why did I feel at home the first time I walked into Saint Peter’s? Because I had been to Saint Josaphat’s. Where was my idea of Teutonic heaviness forged? At City Hall, just as surely as Siegfried forged his sword. And it was all so pleasant — in the learning and the later application. That graciousness is all Milwaukee.

There are connections to other places, too: New York, Virginia, Hollywood. You may be aware of some of them; others, you probably don’t know.

And we may have missed some. Check out these pairings, and if you know of a Wormhole that’s escaped us, let us know!

The Milwaukee Club at 706 N. Jefferson Street in Milwaukee, designed by E. Townsend Mix in the Queen Anne style and completed in 1883 vs. Hampton Court Palace in greater London, begun in 1515 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a favourite of King Henry VIII.

The Button Block on Water Street in Milwaukee, built in 1882 vs. the Gooderham Building on Wellington Street in Toronto, designed David Roberts, also completed in 1882.

Northwestern Mutual Life building on Wisconsin Avenue, constructed in 1914, vs. the temple of Baachus at Baalbek (Modern Lebanon), built ca. 150 AD.

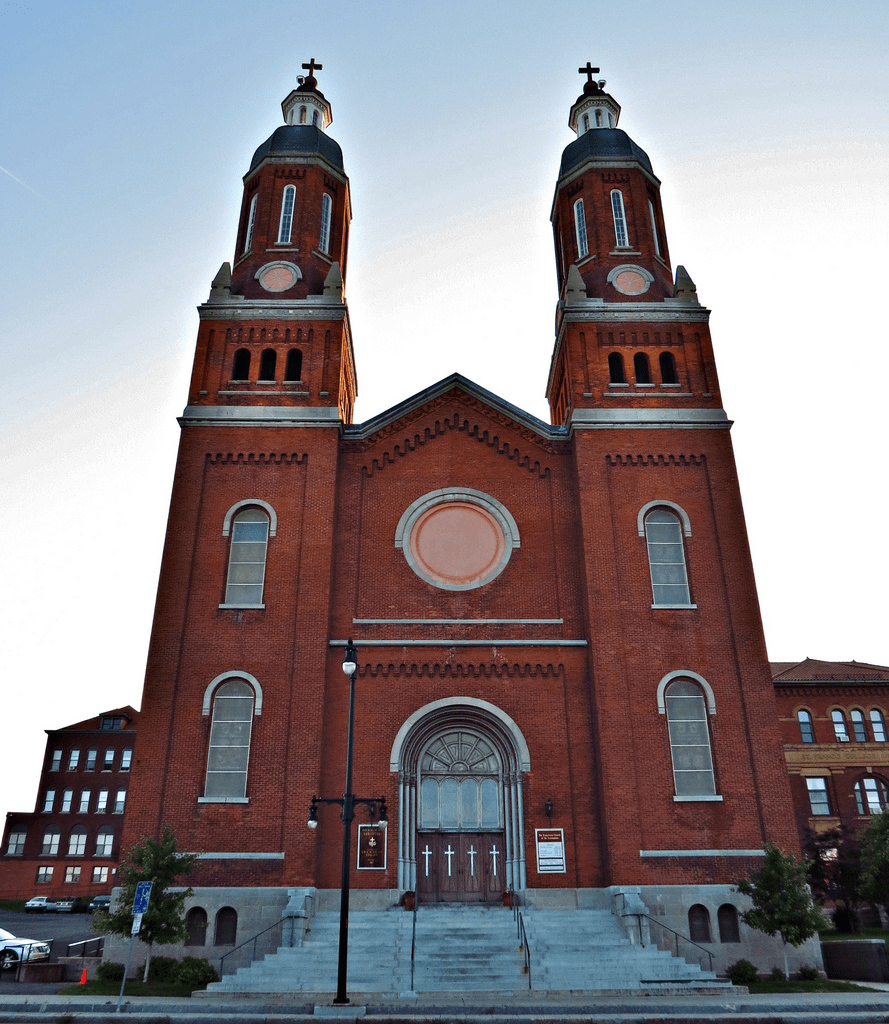

Gesu church on Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee, dedicated in 1894, designed by Henry C. Koch vs. Cathedral of Chartes (France), 12th-13th c.

Milwaukee Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, constructed in 1892-99, designed by W.J. Edbrooke, vs. Old Post Office in Washington, D.C., completed in completed in 1899, also designed by W.J. Edbrooke

Milwaukee City Hall, designed by Henry C. Koch, opened in 1895 vs. Hamburg Rathaus, designed by Martin Haller and others, erected between 1886 and 1897

Chase Tower, formerly known as the Marine Plaza building, on Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee, opened in 1961 vs. The Seagram Building on Park Avenue in Manhattan, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, opened in 1958

Chase Tower, formerly known as the Marine Plaza building, on Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee, opened in 1961 vs. The Seagram Building on Park Avenue in Manhattan, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, opened in 1958

Notre Dame Hall of the Visitation Convent of the (Bavarian-descended) School Sisters of Notre Dame, on Watertown Plank Road in Elm Grove, completed in 1899 vs. Hohenschwangau Castle, southwestern Bavaria, finished in 1855

Notre Dame Hall of the Visitation Convent of the (Bavarian-descended) School Sisters of Notre Dame, on Watertown Plank Road in Elm Grove, completed in 1899 vs. Hohenschwangau Castle, southwestern Bavaria, finished in 1855