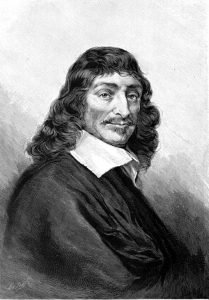

One of the most enjoyable books I’ve read recently is Dr. Peter Kreeft’s Socrates Meets Descartes. Kreeft presents a “conversation” between these two fathers of ancient and modern philosophy. (He’s actually written a series of outstanding books that present a “conversation” between Socrates and various intellectuals and philosophers throughout history.) An often humorous read, Socrates Meets Descartes starts off with René Descartes, who just died. A bit confused, he finds himself in Purgatory. Out of nowhere, Socrates appears before him and characteristically, begins to cross-examine him about his revolutionary work, Discourse on Method. A big part of Descartes’ period of purgation consists in being grilled on his philosophical theories by Socrates to see their fallacies and (disastrous) logical, long-term consequences.

Why is Descartes so revolutionary? Along with Francis Bacon, he introduced the modern idea that the goal of knowledge is to gain mastery and dominion over nature. This may sound innocent enough. But when it is contrasted with the Classical (Socratic, Aristotelian, Thomistic) view, which says that the goal or end of knowledge is virtue, self-control and the conformity of the soul and intellect to nature and reality, the difference becomes more clear. Perhaps without knowing how disastrous it would play out, Descartes planted a seed that is coming more into fruition by the day. Society today has come down decidedly on the part of Descartes when it comes to the purpose of knowledge. The list of typical headlines in the news prove this. One of those headlines struck me more forcefully than others: Survival of the richest: Could an elite class of SUPERHUMANS upgrade their way to immortality? We’ve all heard of the transgender movement. Brace yourself, because apparently, the next step in this downward spiral in Western Civilization is transhumanism. Just when you thought it couldn’t get any more bizarre, here’s a taste of the kind of language we should expect to hear.

Istvan [transhuman advocate] believes that people have the right to modify their bodies in any way they want – as long as these modifications don’t hurt anybody else.

Moreover, he believes that people can give themselves significant advantages in life by “upgrading” their bodies using technology.

. . .

“In 15 to 20 years it will be very common for someone to say, ‘I had an upgrade on my arm, and I’m happy about it, and I’m looking for the next model,’ sort of like we look for the next model of iPhone.”

Secular, atheistic immortality. Sound appealing to you? We’ll return to this in a minute.

Another pillar of Cartesian thought is dualism between the body and mind. Descartes says that the mind (without the body) is the hub of our essence. Thought itself proves our existence, so the mind is what makes us essentially who we are, and hence the famous statement from Descartes, Cogito ergo sum. “I think, therefore I am.” In the course of his examination, “Socrates” dismantles this idea in the book as well. But the repercussions of this Cartesian understanding of the end of knowledge and his mind/body dualism have wrought enormously negative consequences for our society. The trans-fill-in-the-blank movement traces its philosophical underpinnings to this theory.

The body is no longer an integral part of what makes human beings human, and ethics has been reduced to utilitarianism. What is good, even the highest good, is what is useful and vice versa. According to the very Cartesian view of the transhumanist, the body is basically an iPhone, a cold appendage that can be manipulated by the mind. As a mere object, cold and distant from our true identity, the body can be “upgraded” with the assistance of technology. While those who reject God will enthusiastically embrace this prospect, the rest of us should shudder. Why is this view so dangerous and terrifying? One of the final “exchanges” between Descartes and Socrates shows us.

Descartes: Well, that [conquest of death] would be the supreme triumph of “man’s conquest of nature”, would it not?

Socrates: Indeed it would. And nearly four hundred years after you wrote this book, the dream began to rise again from its grave.

Descartes: Why do you use such a ghastly image?

Socrates: I will tell you outright, without any cross examination: because it is a ghastly idea. It is, in fact, an idea that, if it were implemented, would be the single most disastrous idea in the entire history of the world since the idea to eat the forbidden fruit. In a sense, it is the same idea: the idea of sneaking past the angel’s flaming sword, back into Eden, to eat the fruit of the tree of life and immortalizing the state mankind fell into by eating the fruit of the other tree, the forbidden one.

Descartes: Why is that such a disastrous idea? Because it is impossible?

Socrates: No, because it is possible.

Descartes: But that owuld be paradise on earth

Socrates: No, it would be Hell on earth.

Descartes: I am appalled and astounded to hear that. I do not understand.

Socrates: Have you ever smelled an egg that never hatched?

Descartes: I have indeed.

Socrates: Then you have smelled the world you hoped for.

Descartes: You mean we are designed to “hatch”, to die and resurrect.

Socrates: Yes.

Descartes: So a world without hatchers would be a world of rotten eggs.

Socrates: Exactly. But the grace of God . . . gave you the gift of an early death, so that you did not have the time to create that world of rotten eggs, or to live in it.

We are made for immortality, but not the sterile, narrow kind envisioned by a godless world. As “Socrates” put it, that kind of immortality would be Hell.

Through the colorful, intelligent, combative and at times playful exchange between the two characters in his book, Peter Kreeft gives Descartes the benefit of the doubt that, as a God fearing man, he would have been mortified by the horrible consequences and ideological pathogens that have resulted from his ideas about man and nature. But we should take note.