This is the homily I wrote for this morning’s Mass for an English-speaking congregation in Switzerland. I don’t think you can ever have too many perspectives on the Gospel, so for what it’s worth I wanted to share these reflections with you. Most of the ideas in this homily are old and far from original, but I think that’s what makes them interesting. Homilies are for the ear, so this might be hard to read off the screen. Maybe it’s best to try it out loud? Do it in the spirit of “laetare” — rejoicing in the heart of Lent.

Well, it’s Lent. It’s the Fourth Sunday of Lent. We are deep in the season where we face our sins and tighten our belts and bow in prayer and vow to repent. It’s been hard, and there’s more ahead. So you might be surprised when you hear what the Church has for us today. All over the world, in its universal prayer for this Sunday, the Church sings what it has sung for centuries. It’s from the sixty-sixth chapter of the Book of Isaiah, and we sing: Rejoice, Jerusalem, city of peace: you who cried in sadness: come to her, and drink in gladness. Rejoice, and let sorrows cease.

The text in the Latin translation is beautiful. It says, Laetare Jerusalem, gaudete cum laetitia, qui in tristitia fuistis. Laetare, rejoice. And this is called Laetare Sunday. Rejoice. Holy Week is not so far away. It’s still night, but we can see the first streaks of dawn in the sky. Rejoice. And the light of dawn is rose-colored or pink, when you first start to see it in the clouds. And that’s why priests traditionally wore pink robes on this day. You have to be a really brave priest to wear pink vestments.

The dawn is coming. So we have hope. With God, there is always hope. And we look forward to the Resurrection. But we can’t rush to Easter. We can’t rush past the cross. The way of the cross lies in front of us. And in these weeks in the heart of Lent we are on that path, we are all on the road, right next to Jesus.

A few weeks ago we were on the mountain, on Mount Tabor, far up in the northern part of the Holy Land near Galilee, and we saw the awesome transfiguration, when Jesus became brilliantly white and shone with light. But we could not stay on that mountain peak. We came back down to the plain. We kept walking with the Lord, on those dirty paths, walking southward, downward toward Jerusalem.

Last week we came to Samaria and we met the Samaritan woman at the well. And she was so sad and so cynical that at first she only laughed at Jesus. But the Lord changed her heart. She was at Jacob’s well, and you can find that well today in the city of Nablus, which is in Palestinian territory. We’re heading down and we’re getting closer and closer to Jerusalem. No one know what will happen there, but the Lord does. And he doesn’t run away from the cross. He walks closer.

And today, at last, we break out onto the streets of Jerusalem. Onto the streets of the world’s most holy city, but also the world’s most tense, most intense, most nervous and edgy city. The streets are crowded, and at this time even more crowded, because the feast of Passover is coming. They tell us that in Jesus’s time the population of Jerusalem doubled at Passover. Jewish pilgrims came from all around the empire. And it wasn’t just Jews: Greeks and Egyptians and people from Syria and Italy came, just to look, just to marvel at what was happening. Up on Mount Moriah in the middle of town was Herod’s temple, made of white marble that shone in the sun. Sacrifices were made on the altar, with thousands of animals going up and thousands of pilgrims pressing around. Priests moved quickly to slaughter goats and cattle and tend the fire and send up the smoke.

People were buying food, buying sandals and looking for lodgings or a bath or looking for their children and the streets were overflowing. And if you were in charge of the city, if you were a High Priest like Caiaphas or part of the elite like the Pharisees, you felt a lot of pressure to keep things cool. Because the Romans were watching and they didn’t tolerate disorder. They wanted control. But one thing that none of us can ever control is the Lord. The Lord Himself is about to come into Jerusalem, and no one knows what is about to happen. But God knows. God moves in a mysterious way his wonders to perform, as the old English hymn says.

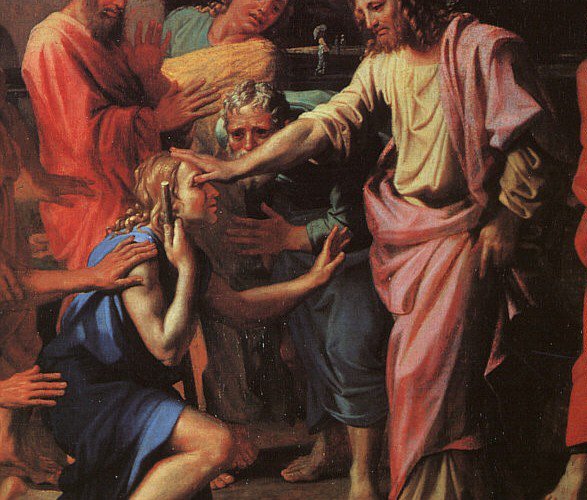

And here comes Jesus. Here is Jesus in that crowd, in those streets. It’s noise all around, but the Lord sees everyone and the Lord knows what he is doing. And the Gospel says, “As Jesus passed by he saw a man blind from birth.” Blindness. Darkness from the day he was born. We know this man must have suffered. But we also know he was one of many beggars and one of many blind and disabled and wounded people on those streets. But this man is the right man. And the Lord stops right in front of him. Our Lord and Our Savior stops for this man sitting in the dirt on the street. And he bends down. Jesus lowers himself until he is right on the level of this man, right down in the dirt. And he mixes his spit with the dust on the street. And he makes clay.

Do you remember the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible, back in the Garden of Eden? That’s where the Lord first bent down over a man, bent down into the dust and made clay and lifted up the man he had made. It says: “the LORD God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being.” Tradition tells us that the Lord mixed his spit with the dust of the earth to make clay, and from that clay he made Adam. And on Ash Wednesday, each one of us was told: remember, man, that you are dust and unto dust you shall return.

And here is this blind man, this beggar in the street, being smeared with clay by the Lord. Jesus takes the clay and rubs it over the man’s eyes. He anoints this man. He smears him with mud like priests are smeared with holy oil. And through the ministry of the church, by the hand of the priest, each one of us has been anointed. At baptism, we were anointed, at our confirmation, we were anointed. And when we are sick or near death we will receive another sacrament and again we will be anointed. Smeared with ointment, just as this man was smeared with clay. Anointed, just like this red-haired boy called David in the first reading today was brought out of the fields and anointed by the prophet Samuel. And he became a king.

So here this thin, weak man who is terribly poor and totally blind stands in for every one of us. Remember what Jesus said: this man is sitting in the path “so that the works of God might be made visible through him.” Jesus is showing us. He’s doing it again. He is showing us in this physical, earthly way exactly how each one of us can be saved.

But Jesus isn’t finished. He has more to tell this man: “Go wash in the Pool of Siloam”. On one level, it’s simple. Jesus has just smeared clay on this man and now he’s telling him to wash. It’s pretty clear. But what is this Siloam? On one level, Siloam was a big artificial pool. It was a real place, and archeologists have uncovered it on the eastern edge of today’s old city of Jerusalem. It was a vat of fresh water that pilgrims used to wash themselves before going to the temple. We have even found the pipes and the drains of this pool of Siloam. And the blind man was probably sitting in one of the streets right next to it. But that’s only one level of the Gospel. The scriptures today give us a clue to the deeper level. It says “’Go wash in the Pool of Siloam’ —which means Sent—.” The Gospel writer actually steps into the story to tell us that Siloam בריכת השילוח means sent (from the verb לשלוח). What does a Christian think when you hear the word sent? Who is the one that was sent? Sent by the Father, sent to save us. It is Jesus himself.

God moves in a mysterious way. Siloam means sent. And so in washing in Siloam, this blind man is washing in the one who was sent. He is immersing himself in Christ. And you did exactly the same thing. You did exactly the same thing, because the pool of Siloam, and the waters of our Savior Jesus Christ, are the waters of the font of baptism, which is that pool of water you can see in the baptistery in the back of the church over there. That is our Siloam with its waters blessed with the power to heal. That’s where we wash our sins away. And that is where our eyes are opened.

And so we open our eyes. And we look. We open our eyes and look again. There is the narrow street in Jerusalem at the beginning of today’s Gospel. There are the crowds, the pilgrims and the foreign visitors crowding the path and heckling and hustling and pushing through. And there is a blind man, sitting in the dirt. You see that man and you want to pull away and move on down the road. He looks so miserable that the disciples ask Jesus, “who sinned … that he was born blind?” He’s not a pretty sight. But Jesus stops. He stops and he bends down. He lowers himself and gets down in the dirt, at the feet of this man. Because that blind man is you. It’s me. Its every person who is broken and weak and who can’t see on his own; everyone who needs to be lifted out of the dirt. That man is you. And Jesus stops, for you. He stops in the middle of his path. Because this blind man is the one. This is the one to whom he was sent. This is the one he came to save. You’re why he’s here. You’re why he came. By his anointing and by the waters of baptism and by his suffering and his sacrifice, he will take you and unite you to himself, perfectly, forever.

God moves in a mysterious way his wonders to perform. And the disciples and the pharisees and everyone in that street can do nothing but wonder and stare in silence. But when you are healed, and when you have washed and recovered your sight, then they will come back to you. Then they’ll come to you, and they’ll stop you in the street, and they will question you, just as they questioned this man. And they will ask you “What do you have to say about this Jesus, since he opened your eyes?” “What do you have to say?”

Well, today we have something to say. We are not afraid. The Psalm today said: “Even though I walk in the dark valley I fear no evil; for you are at my side.” And we say, with the psalmist, and with the prophet Jeremiah who tells us to rejoice; we say, as we wait for the Cross and the pain of the passion and we hope for the dawn of Easter morning, we say, and we sing with all the saints that Jesus Christ has anointed and washed and healed and saved, we say with the poet, in the words of the old hymn:

God moves in a mysterious way

his wonders to perform:

he plants his footsteps in the sea,

and rides upon the storm.

Blind unbelief is sure to err,

and scan his work in vain;

God is his own interpreter,

and he will make it plain.

His purposes will ripen fast,

unfolding every hour:

the bud may have a bitter taste,

but sweet will be the flower.

(William Cowper, 1773)

The bud may have a bitter taste, but sweet will be the flower. Hold on. Walk with Christ. Walk to the cross. And walk on through the cross to the morning. Amen.