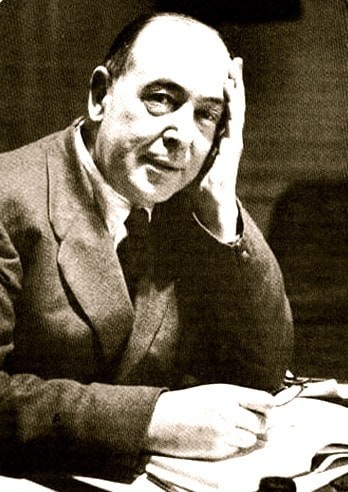

Spiritual reading in the non-fiction category is undeniably invaluable; however, many imaginative souls are far more affected by a beautiful image or a moving story. If you happen to be among the camp of readers more likely to change through visual symbolism, “Till We Have Faces” by C.S. Lewis is your story. Dedicated to Lewis’ wife, Joy Davidman, the 1956 novel is a Christian retelling of the pagan myth of Cupid and Psyche. In the traditional Greek story, a radiantly beautiful Psyche captures the heart of Cupid, the god of Love and son of Venus. Their love is threatened however, by the jealousy of Venus, and Psyche’s own sisters. Despite many trials, and Psyche’s own woeful betrayal of Cupid’s trust provoked by her manipulative sisters, Psyche and Cupid are ultimately restored to each other, and Jupiter transforms Psyche into a goddess. While the myth is focused on the immediate tale of the two lovers, Lewis’ recount of the story purposes to explore the psychology of the relationship between Psyche and her eldest sister Orual, and between Orual and the gods.

Lewis’ princesses, Orual and Psyche live in the kingdom of Glome, to the far north of the “Greeklands”. With their mothers dead, and their father, King Trom violent and unfeeling, the two girls, along with their middle sister Redival, find themselves under the mentorship of a Greek slave, The Fox. Now, the Fox is the quintessential philosopher, educating the princesses in the ways of reason and Nature; in fact, the conversation between Orual and The Fox is reminiscent of the dialogues of Plato. In contrast, Glome itself is under the patronage of the goddess Ungit, who demands bloody sacrifice to appease her anger and bring fruitfulness to the land. The dichotomy between the Fox’s Socratic teachings and Ungit’s appetite for blood demonstrate two pagan approaches to life, namely, that of the philosopher and that of the poet. It is worth noting that many ideas of the Fox and of the cult of Ungit echo our own post-modern era; the Fox rationalizes suicide, “Have I not told you often that to depart from life of a man’s own will when there’s good reason is one of the things that are according to nature?”, while Ungit requires the kingdom, “in a bad year,… to cut someone’s throat and pour the blood over her”.

Orual’s understandable fear of the blood-thirsty Ungit is a continuous thread throughout the novel, but she finds refuge with Psyche beneath the protective grove of pear trees where the Fox gives his philosophy lessons. There, Orual’s love for Psyche blossoms beyond that of a sister:

I wanted to be a wife so that I could have been her real mother. I wanted to be a boy so that she could be in love with me. I wanted her to be my full sister instead of my half sister. I wanted her to be a slave so that I could set her free and make her rich.

Unfortunately for Orual, the kind of love that seeks to control the beloved always leads the lover to great unhappiness, and when the god of the Mountain’s pursuit of Psyche’s heart takes her away from Orual, the isolated methods of the Fox and of the gods fail to adequately answer Orual’s cry of grief. She admits,

I could not find out whether the doctrines of Glome or the wisdom of Greece were right. I was the child of Glome and the pupil of the Fox; I saw that for years my life had been lived in two halves, never fitted together.

It is of no importance to Orual that Psyche is happy with her new husband, for she is consumed solely with her own loss, and begins her formal complaint against the gods.

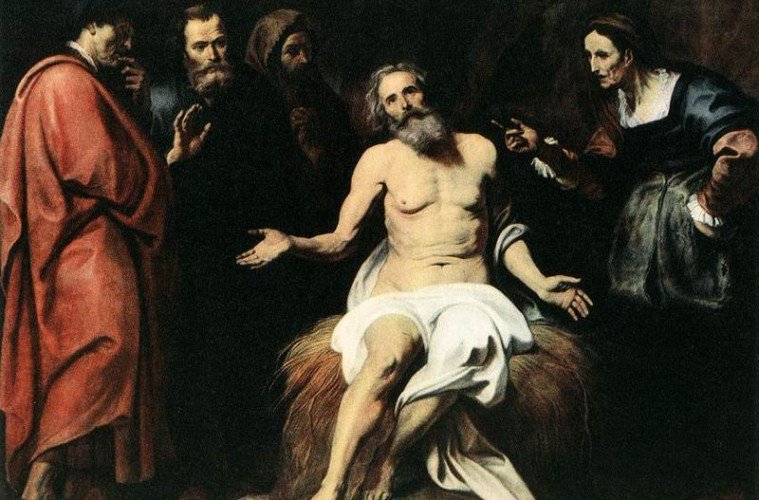

Much of the commentary I have read on “Till We Have Faces” discusses the various kinds of love represented in the story. Without a doubt, Lewis used ideas from his work, “The Four Loves” when sketching his characters; one could even say that “Till We Have Faces” is the fictional version of “The Four Loves”. Other commentators suggest that he drew from the book of Job. Orual’s complaint against the gods both resembles the lament of Job, and also goes a step further to accuse the gods of ill-will and “trickery”: “It was of course the gods’ old trick; blow the bubble up big before you prick it”.

Like Orual, we construct ideas of what we think our life should be, or how we think our relationships with others should look. The moment will arrive when our dreams, the dreams of poets and philosophers, are shattered, and we are stripped bare like Job and Orual, suspicious of God and His motives. For some, it may come in one tremendously painful moment, such as at the death of a loved one, while for others, it may be over a serious of dull, repetitive instances in which we are passed over for someone, or something else. We grab at life, trying to make it our own, and in spite of the fact that it belongs not to us, but to God. In Orual’s complaint against the gods, she asserts with force: “Did you ever remember whose the girl was? She was mine. Mine! Do you not know what the word means?”. Interestingly enough, the gods never answer Orual. Instead, a sweeping reversal of perspective brings Orual to the realization that her complaint is terribly inverted. Everything she had supposed about the gods, the people she loved, and herself was false when unveiled before the presence of the god of Love from whom she had sought to free Psyche. All her life, Orual complained, “They would give no clear sign, though I begged for it”; yet, in the presence of the god so full of love, so full of kindness and mercy, her response is, “I know now, Lord, why you utter no answer. You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away”. In the face of our own sufferings, should we not also have the same response to Christ?