Part One: The Modus Vivendi of Catholic Politicians

For Millennial Catholics like me, the shyness of the American Episcopate in dealing with the Democratic Party is truly bewildering. For my entire lifetime the Democratic Party has been aggressively pursuing policies that contradict the faith and even basic human rights. Abortion is a barbaric practice that will go down in history as a heinous crime, in good company with slavery and genocide. Yet pro-choice politicians receive Communion, while the laity are scolded from the pulpit to support life issues of a farcically lower priority.

There is no excuse, but there is an explanation. The answer is a concoction of inherited alliances, institutional inertia in the face of a rapidly changing political scene, and cultural memory. Left to fester, the mix becomes a toxic brew that leaves the drinker lukewarm.

When the United States was founded, religious liberty may well have been in law, but America was as hostile to Catholicism as a nation could get. Laced with puritan heritage, founded by freemasons, and birthed by the British Empire, the young country was not exactly a welcoming place for the Church. Catholics were a small and distrusted minority.

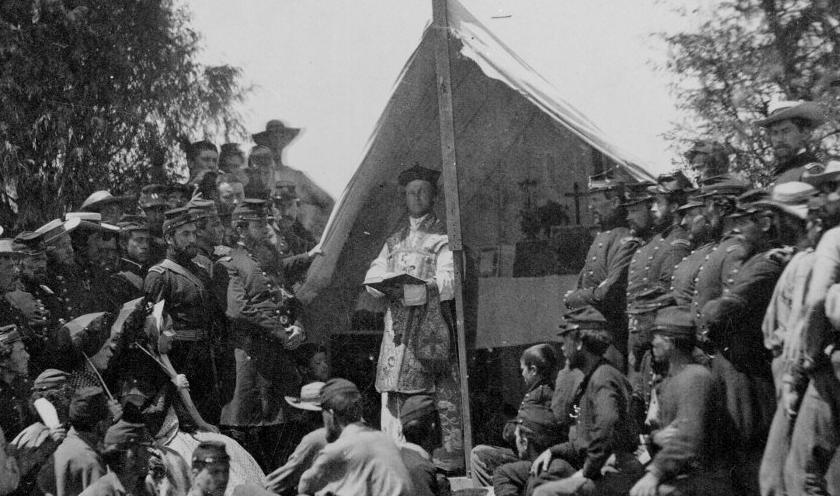

The arrival of immigrants from Ireland, Germany and other Catholic European countries brought the problem to a head, and the 19th century would see anti-Catholicism in the United States reach its zenith. Catholic participation in the American Civil War, filling out the thinned Union ranks, along with surging numbers of eligible voters demonstrated to the powers that be that Catholicism was here to stay. In the big cities, Irish, German and Italian immigrants made their influence felt politically through the Democratic Party, which had reached out to these marginalized groups to build its power bloc.

The alliance with the Democrats worked, and mighty political machines were built in metropolises across America, such as Milwaukee, Boston, and New York. In 1928 the Democrats nominated Al Smith, a Catholic, as their presidential candidate, and he picked up more than a third of the vote. In 1960 John F. Kennedy was elected President. This finally granted Catholics a seat at the table: real power. That power came with a price, however. American politicians welcomed Catholic votes but not Catholicism.

Kennedy needed to win over Protestants who were hostile to Catholicism and quash suspicions about “dual loyalty” to America and Rome. Dual loyalty accusations were often and effectively used as a political attack to handicap Catholic politicians. Kennedy countered not only by forswearing dual loyalty to Rome, but forswearing Catholicism itself. Thus we have the kernel of the “Personally opposed but…” canard. This is the modus vivendi (way of life) for Catholicism and American politics:

“I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me. Whatever issue may come before me as president — on birth control, divorce, censorship, gambling or any other subject — I will make my decision in accordance with these views, in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be the national interest, and without regard to outside religious pressures or dictates. And no power or threat of punishment could cause me to decide otherwise.” – John F. Kennedy, September 12th 1960, Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association

This modus vivendi exists to this day and there are penalties to deeply held faith in the public. One only has to look at the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to see how Catholics who publicly practice their faith are treated. Senators Sanders and Feinstein subjected her to an un-American interrogation about her faith, and there was not much protest. Justice Antonin Scalia faced public criticism for his traditional Catholicism that would not be tolerated had the Justice held any other belief.

This compromise on values was a monkey’s paw that profited Catholicism for less than a decade. During the late ’60s and early ’70s, the historically Catholic Party veered further to the far left. Old allies and friends such as Ted Kennedy and Al Gore, along with the power brokers in local government, changed their “public” position on abortion with a clear conscience, and pro-life Democrats were squeezed out. The episcopate, most or nearly all lifelong Democrats themselves, were saddled with its customary inertia. Efforts for the abolition of abortion and the defense of marriage were disorganized and unfocused. When criticism was pointed and direct, it was often only individual bishops and could be easily dismissed.

Mario Cuomo in the 1980s was famously able to collect Catholic votes on his way to the New York governorship while supporting abortion with little consequence. Similarly, almost all modern Catholic Democrats will claim private opposition but vote in accordance with their Party. In 2017, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Tom Perez, made the exclusion of Pro-Life Democrats practically de jure. Only holdouts in red states, such as Catholic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, buck the Party line.

On the other side of the aisle, it was not until 1980 that the Catholics and Protestants were able to make enough common cause to truly unite under the Republican banner. Today, maybe fifty percent of Catholics vote Republican. Even still, they are scattered across the country while Catholic Democrats are heavily concentrated and influential in their respective regions. Catholic Democrats view loyalty to the Democratic Party almost as part of their cultural heritage. There certainly are not generations of entrenched support or the legendary Catholic political dynasties that you see in the Democratic Party with the Republicans. Many Catholics still view their relationship with the Republican Party as a marriage of convenience, and there is vocal discontent with lack of progress on the abortion front.

So why the history lesson? Let’s put this in perspective. Most of the episcopate grew up and spent at least their early careers where the Democratic Party would have been either at least not expounding anti-life positions, or when there was a sizable enough minority of pro-life voters and candidates where one could feel justified in continuing to give it support. Theodore McCarrick, Cardinal Cupich and Cardinal Wuerl’s respective generations would fall into this category. They almost certainly grew up in Democrat households with Democrat friends and made alliances with Democrat politicians back when there was no moral issue about doing so.

For the upper echelons of the American hierarchy, renouncing the Democratic Party and its works will have a personal, as well as a very public cost. Many partnerships, alliances and even relationships would have to be sacrificed. The masses of non-practicing but culturally Catholic, which have large populations in the historic sees, would be outraged. Thus the temptation to punt the inevitable confrontation between the Democratic Party and Catholicism to the next generation becomes all-powerful.

Things have accelerated in the last few decades as the Democratic Party has embraced anti-marriage as well as anti-life positions. This presents problems, especially when the Party turned hostile towards religious institutions after the 2008 election. The outrageously anti-Catholic behavior by Catholic politicians has made it more difficult for the episcopate as a body to obstruct a certain and extremely “inconvenient” law of the Church aimed straight at the heart of the modus vivendi: Canon 915.